Where should we build City Hall

Heated public debate over the ideal location for Calgary’s City Hall

In 1903, Calgary’s Board of Trade began calling for a new municipal building worthy of the future metropolis they knew their city would become. The Daily Herald reported in March 1904 that the interior of the old Town Hall was being renovated to make it more comfortable for civic officials. However, public opinion on the matter was clear:

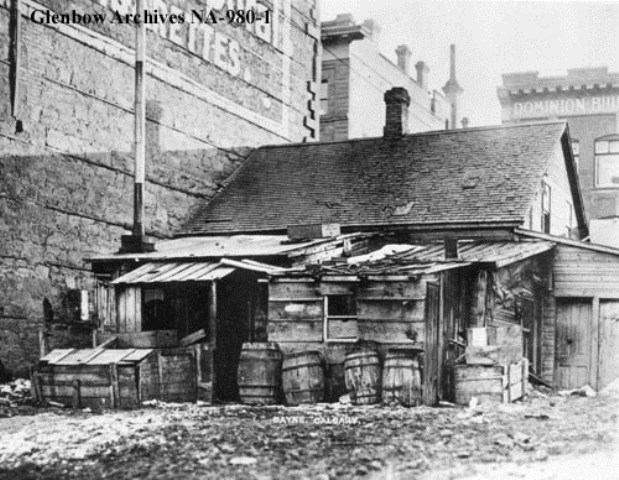

“What? fixing up that old ramshackle building,” demanded one of the gathering. “It’s a shame to spend money on such an eyesore of a building. They should burn the place down instead of trying to fix the thing up.”

When it was still in use some six years later, the Calgary News-Telegram labelled the structure “a disgrace to the city.” It should be no surprise that efforts were mobilized to replace the building. “The general public are viewing with a good deal of satisfaction the proposal to erect a new city hall,” the Herald commented in 1904, when the matter was first given serious consideration, but added this qualification: “...provided the location to be central and easily accessible.” Failure to agree on the proper site was to hold up the project for years.

During a 1904 city council debate, some aldermen objected to the idea of a new city hall “because civic finances are not in a position to warrant such a project”; others were adamant that “the city’s business had been transacted in the present shack long enough.” Opponents of a 1904 bylaw to provide $75,000 for the construction of a city hall pointed out that council had no idea how much money the project would consume; one alderman thought a new city hall could be built for just $30,000. As well, the bylaw specified the existing Second Street E. (later renamed Macleod Trail SE) site be used, offering no alternatives. Council defeated the bylaw on second reading, but it appointed a committee to investigate other possible sites. Some of the suggestions included the southeast corner of Atlantic (Ninth) Avenue and First Street E., belonging to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR); and a site on First Street W., also owned by the CPR.

The committee set its eyes on an even better option, however, and in April 1904 it was authorized to purchase several lots owned by the Church of the Redeemer, for $20,000. A bylaw was prepared, but this site too was ruled out when ratepayers voted against it in June. The matter took place in the aftermath of a scandal, in which the City had sold 500 lots without public advertisement and at a fraction of their value, many to the friends of aldermen. Irate taxpayers had seen the sale as a “land-grab” and called for an investigation, after which two aldermen, one auditor, City Clerk Charles McMillan and City Solicitor J.B. Smith (died 1910) all resigned.

City Hall’s existing site came up once again in August 1905, but few people saw the merits of a location that, by that time, was considered the fringe of a business core that had grown primarily to the west. The site was also located in a low-lying area, which, as the Herald saw it, was “excellent for warehouse or livery stable purposes but utterly worthless as a city hall site.” As a result, the bylaw again failed to gain the two-thirds majority needed for approval.

To overcome the impasse, in October 1905 the Board of Trade joined forces with the city council committee in a renewed effort to identify a suitable location. The joint committee called for tenders to settle the “vexed question,” and it reviewed more than a dozen sites. Finally, it came up with a clear favourite on Centre Street. The catch, however, was that it would cost ratepayers $30,000 to expropriate the lots—and because of glitches with the property owners, the proposal stalled. But it was a question that would not die, as the Herald stated, “so long as that monument of civic poverty, which we have learned to call the city hall, stands.” To some extent it was a battle between the “east end” and the “west end”, with council members, citizens, and media divided along geographic lines. The Herald lobbied hard for the Centre Street site, which was located across the street from its own offices, while Albertan editor William M. Davidson (1872–1942) preferred to keep the existing site and get on with construction. Finally in March 1907, tired of the long controversy, Calgarians approved Bylaw No. 724 to borrow $150,000 for a new city hall and police station—on the present site, where Calgary’s Town Hall had been since 1885.

In future years, the question of the city hall site would resurface when various new civic centres were proposed. As early as 1913, Thomas H. Mawson (1861–1933) envisioned a lavish new city hall as part of a mall on Fourth Street W., just south of Prince’s Island, but his plans were shelved when Calgary’s real estate boom turned bust that year.

Following the Second World War, Mayor Donald H. Mackay (1914–1979) announced a new civic centre as his top priority. Several sites were considered, including Riley Park, Mewata, and Eau Claire—but the $9 million price tag was too high and on April 15, 1957, council vetoed the proposal. Mayor Mackay refocused his plans on a more modest city hall, but that too was rejected in October 1959 when ratepayers voted down a $4 million bylaw to build on the site of James Short School. Instead, under the leadership of Mayor Harry Hays (1909–1982) the following year, council approved a “practical” new office building adjacent to City Hall.

Mayor Ross Alger (1920–1992) made a third attempt to build a major civic centre complex in the late 1970s, hiring architects Raymond Moriyama (born 1929) and Harold Hanen (1935–2000) to draft plans. However, the estimated price of $271 million was too high, and the proposal for the five-block complex centering on what is now Olympic Plaza was once again defeated by plebiscite in 1979. Though it never quite matched the grandiose dreams of what city boosters envisioned, Calgarians had reaffirmed the existing site as the best location for City Hall.