Sandstone quarries

For those who commute to City Hall via Crowchild Trail, here’s a thought: You might be unwittingly retracing the path of the building’s very stones.

Before 1967, when Twenty-fourth Street SW was transformed into the Crowchild Trail freeway, it was still possible to see the remains of a sandstone quarry, one of about fifteen that operated in or near Calgary’s present city limits prior to the First World War. The Wm. Oliver and Co. quarry (also known as the Bankview Quarry), established around 1901, operated in what had been a north-south oriented gulley that traversed Seventeenth Avenue W. just east of the present Crowchild Trail SW. The Richmond Road Diagnostic and Treatment Centre, which operates in the old Alberta Children’s Hospital building (1820 Richmond Road SW), now occupies part of the quarry site, which was the source of much of the stone that went into the first phase of City Hall’s construction.

The yellow stones that came from this and other quarries are part of the Paskapoo formation, a geological layer of fluvial origin (that is, related to rivers and streams and their landforms and deposits) that dates back to the Paleocene epoch (66–56 million years ago). They were used for the 1912 construction of Sunalta School (536 Sonora Avenue SW), which stands a short distance northwest of the quarry site and within view of Crowchild Trail SW.

Industrial use of Paskapoo sandstone dates back as early as the summer of 1885, when the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was quarrying stones from Shaganappi Point west of Calgary (on the future site of Edworthy Park) for use in government buildings in Regina. It might have begun even earlier that year when former North-West Mounted Police officer Joseph Butlin (circa 1857–1924) was already preparing to establish his sandstone quarry along the Elbow River, opposite what is now Riveredge Park in Calgary’s Britannia neighbourhood. In February 1886, the Calgary Tribune (forerunner of the Calgary Sun) enthused over the local resource:

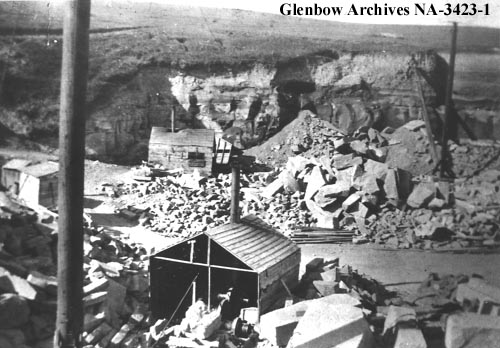

View of stone quarry located at Glenbow, AB, circa 1910. Courtesy Glenbow Archives

There appears to be a considerable difference of opinion regarding the quality of the stone that is now being quarried here for building purposes. It is a sandstone, soft and easily dressed, and if, as it is contended, like the Ohio stone, it will harden on exposure, it is a settled fact that Calgary is possessed of a building material at its very doors, equal to the best in the world, and sufficient of it to build a city the size of old London.

Two substantial, adjacent sandstone buildings were already completed or nearing completion by November 7, 1886, the day of Calgary’s great fire. Most of the town’s buildings were still built of wood, and the loss of approximately eighteen structures in one day gave new impetus to construction of fire-resistant sandstone buildings. This led to the establishment of new quarries and the expansion of the stone products manufacturing industry, which involved cutting, shaping, and finishing stone blocks. By the 1890s, more than half of the skilled tradesmen in Calgary were stonecutters or masons, many of them of Scottish origin with generations of family experience in stone working.

Calgary actually became known as the Sandstone City back then. In an 1891 feature on Calgary, the Globe (the Toronto newspaper later renamed the Globe and Mail) stated:

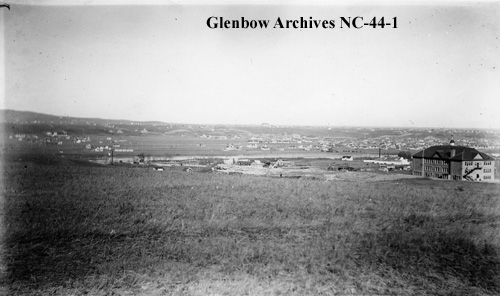

View of Calgary, circa 1910-1915. Looking north, north-east; Sunalta School, right; Bow River in background; Eau Claire Lumber Company to left of school; Oliver’s sandstone quarry, centre. Courtesy Glenbow Archives

Calgary is almost a model town. The hills surrounding it are underlaid with a very superior quality of sandstone, easily worked, and which hardens when exposed to the air. This stone is being largely utilized in building up the town, and Calgary will doubtless yet be called

THE SANDSTONE CITY.

Calgary’s quarries and their owners/operators included:

- CPR quarry (circa 1885): The first of four quarries established in what is now Edworthy Park.

- Butlin Quarry (circa 1886): Located on Butlin’s homestead in or near today’s Elbow Park district.

- Wesley Fletcher Orr’s quarry (circa 1886): Located in or near the Bridgeland district, near the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers. Orr (1831–1898) later served as Calgary’s eighth mayor from 1894–97. The motto he chose for Calgary, “Onward,” stands in relief in the sandstone entrance arch at City Hall as part of the municipal coat of arms.

- Bow Bank Quarry: Three separate quarry sites established by homesteader Thomas Edworthy (1856–1904) around 1888. After Edworthy’s death, his widow leased at least one quarry site to John Bone (1851–1919) and A. Leblanc, who operated at this location from 1909 until 1914.

- Peter Smith’s quarry (1892): Located along the Elbow River four kilometres south of Calgary.

- Elbow River Quarry (circa 1895): Located along the Elbow River in the Ramsay district. It was established by John McCallum.

- Sunnyside Freestone Quarry (circa 1896): Located in the Sunnyside district; established by John McCallum.

- Colonel Thomas Sheppard Barwis’ quarry (circa 1896): Located on Barwis’ homestead north of the Bow River near Prince’s Island.

- Bankview Quarry (Wm. Oliver and Co., 1823—16 Street SW, ca. 1900-15): Located in a north-south gulley near Summit Street SW, traversing Seventeenth Avenue SW. William Nimmons (1824–1919), who homesteaded and later subdivided the Bankview district, owned the property. Nimmons had been held captive at Red River during the first Riel Rebellion in 1869–70, and he escaped. Nimmons leased the quarry to William Oliver (1858–1940), whose concern operated as Wm. Oliver and Co. Oliver evidently later operated the quarry as part of the partnership of Gilbert, Bone and Oliver (in partnership with William Gilbert and John Bone).

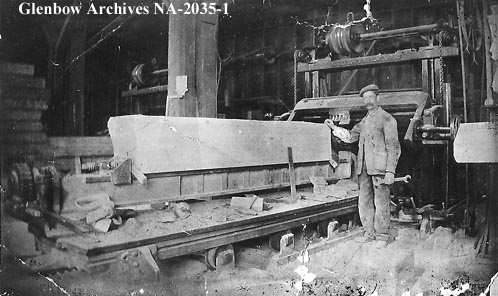

Quinlan Carter’s stonemason’s shop, circa 1911. James Fairley, stone planner, stands in front of Anderson planer. Courtesy Glenbow Archives

Calgary’s quarries and their owners/operators included:

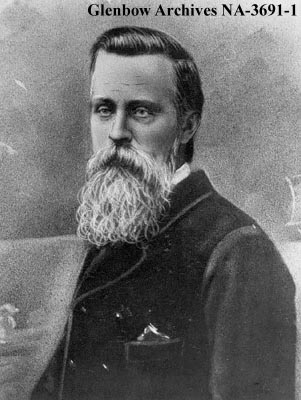

William Nimmons, circa 1913-1919. Nimmons owned the sandstone quarry on 17th Avenue which was managed by William Oliver. Courtesy Glenbow Archives

- John Owens’ quarry (circa 1904): Located near Calgary.

- Glenbow Quarry (1905–1912): Located halfway between Calgary and Cochrane in what is now Glenbow Ranch Provincial Park; a source of stone for City Hall.

- Shelley Quarry Co. (1908–14): Located near Cochrane.

- James May’s quarry (circa 1910-15): Located along Beddington Creek north of Calgary.

- Burnvale Brick Company: Quarry located at Sandstone, Alberta, a short distance south of Calgary.

- Keith Quarry: Located at the Keith railway siding along the CPR in or near the Bowness district.

- John A. Lewis’ quarry: Located on NW21-25-R1-W5M, in what is now the Panorama Hills district; a source of stone for City Hall. The owner was likely John Alexander Lucas (1864–1940), who lived in the Beddington district.

- Felix McHugh’s quarry: Located in the Sunnyside district. McHugh (1851–1912) owned the Far West Hotel (on the future site of the Calgary TELUS Convention Centre), which town council leased in 1884–85 for use as Council Hall while the Town Hall was being built.

- Sandstone Brick and Sewer Pipe Company: Quarry located at Sandstone, Alberta.

- John Goodwin ("Gravity") Watson’s quarry: Located at Brickburn in what is now Edworthy Park.

Over the span of a quarter-century or more, hundreds of buildings were built of sandstone or at least included sandstone as part of their construction material. Dozens of these buildings remain extant in the twenty-first century. Of these, City Hall stands as a late, shining example of Calgary’s re-development as the Sandstone City.

The architectural plans for City Hall, designed by William M. Dodd (1872–1949), called for the highest quality materials and workmanship throughout. Paskapoo sandstone was among the materials that were sourced locally. During the peak of Calgary’s pre-First World War building boom, Gilbert, Bone and Oliver operated jointly, and they were the primary suppliers of sandstone to City Hall. Building receipts show that the Glenbow Quarry was another important supplier.

Richard Cunniffe (1905–1996), author of the comprehensive booklet Calgary—in Sandstone (1969), described the operation at the Bankview Quarry:

Prior to closing down in 1915 William Oliver was employing about 40 men, and the equipment consisted of two steam shovels, two derricks with gang saw, and a piece of equipment called an "orange peel stripper". Hourly wages current at that time were forty-five cents for steam drillers, forty cents for quarrymen, sixty-five cents for stone cutters, and thirty-two to thirty-five cents for labourers. Rough blocks of stone, up to seventy cubic feet, sold for about one cent per foot delivered in Calgary, and rubble was $7,000 per cord.

Oliver sandstone quarry, circa 1915. Located in a gully on either side of 17th Avenue S.W. Courtesy Glenbow Archives

The sandstone era came to an end in Calgary in 1915, when the last quarries closed. Contributing factors included the end of the city’s pre-First World War boom, high labour costs, and competition from other building materials, including locally-made bricks, terra cotta, and Indiana sandstone. As late as 1930, Oliver promoted renewed use of sandstone from a source he identified near the future site of the Glenmore Reservoir. "The sandstone industry has suffered greatly," he said at the time, "[d]ue to the fact that in early years stone for buildings was taken from the upper strata and was therefore poor in quality and would not stand up to the weather". The last known example of new sandstone construction in the city was the Memorial Chapel at Grace Presbyterian Church (1009 Fifteenth Avenue SW) in 1962.

The passage of time provided the real impetus for sandstone’s revival. "Sandstone lasts about 100 years," conservation architect Lorne G. Simpson told the Calgary Herald in 2001. Fortunately, by this time, Calgary had a new source for restoration of sandstone buildings. In the 1990s, development of West Hills Towne Centre at Richmond Road and Sarcee Trail SW exposed a seam of sandstone, and a large amount of stone was retained for future use.